BLOG

The Mosel in Transition

Valerie Kathawala

Blog

Germany’s most mythic and misunderstood wine region has always balanced on a knife’s edge. Today is no different. Only the elemental forces have changed. To understand the Mosel requires an appreciation of what animates — and challenges — it. There is a sense of urgency to preserve what has long felt timeless and immutable, but is proving all too susceptible to market and climate shifts. Overall, the current dynamic is one of pressured if positive convergence. There are peerless steep slopes where growers set global benchmarks for Riesling. There are forgotten side valleys. There is virtuosic skill honed over generations. There is raw, fresh talent. For decades, these existed in a hierarchy of tested value. Today, the deck is shuffled. Wines from a 14th-century estate may be as coveted as those of a start-up. In some cases, the ancient winery and the start-up are one in the same.

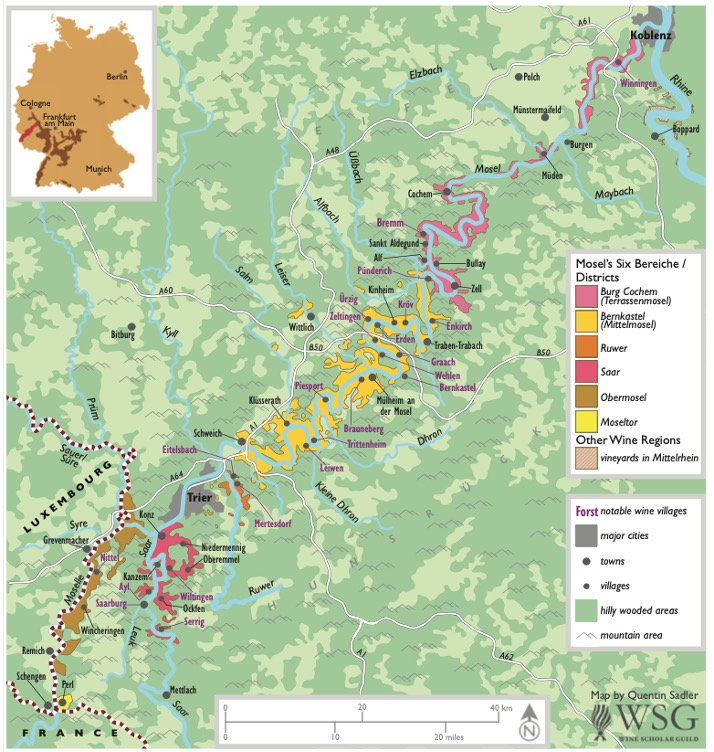

The Mosel is Germany’s fifth-largest wine region, with 60 million vines planted over 8,446 ha. But the soul of the Mosel is its individuality and small-scale structure. Over 2,000 growers cultivate a patchwork of parcels. This works out to an average vineyard area per winery of just 3 ha, roughly the size of three soccer fields. Even iconic estates like Joh. Jos. Prüm and Egon Müller have made their names with small to mid-sized (if extremely prestigious) holdings.

A Cultural Landscape

The Mosel is home to some of the most well-established and widely recognized landscapes, terroir and estates in Germany. Its growers produce inimitable wines across a spectrum of styles, from canonical to iconoclastic. Today the range spans bone-dry, sparkling, red, amber, rosé and — most famously — wines of laddered sweetness, with rungs made of equal parts sunshine and acid. A throughline that has emerged over the past decade is a turn away from the efficiencies of machines and the safety of chemical control. Handcraft and individuality are bywords.

But a sustained decline in wine consumption, rising costs, a shift in labor structure, bureaucracy, climate change and the specific and unrelenting demands of steep-slope viticulture are testing producers. This is forcing what industry experts say is a transition of a magnitude not seen since WWII.

While some wineries are well-positioned to withstand a market shakedown, there will be many for whom wine production is no longer economically viable. A wave of insolvencies and vineyard reductions is almost certain to be the near-term result. Last year, roughly 170 ha of Mosel vineyards were taken out of cultivation. Mostly, these were small, inconveniently scattered plots. In the Mosel, steep slopes are defined as those with an incline of 30% or more; more than one-third of the region’s vineyards meet this criterion, making it the world’s largest steep-slope area. Industry experts and producers speak of a likely loss of 20 to 30% of the Mosel’s steep-slope vineyard area in the next few years. This would be an incalculable loss of cultural landscape, ecosystems and way of life.

This is far from declaring that the Mosel is going out of business. It does mean an excruciating closing of doors for some producers. It also means an opening of generational opportunities to growers eager to get their hands on prized plots and ancient cellars. This spirit of opportunity, coupled with producer know-how, is pushing styles in new directions and challenging old ideas of what Mosel wines can be.

What the Future Looks Like from the Vineyard

Jonas Dostert is a small producer in the Obermosel, at the gently rolling southern end of the Mosel Valley. He is keenly attuned to the tensions in play. He grew up on a family estate, but has a newcomer’s sense of possibility. He works in a long-overlooked area, but one where limestone soils and a still-cool climate offer tremendous potential. His estate is young. He positioned himself for a new wine economy from the start: with just 3 ha he works on his own, keeping business costs low and flexibility high. The quality of the Rieslings, Chardonnays, Elblings and Pinot Noirs he produces and the acclaim they’ve received would give any grower confidence about the future. He’s secure in his. But he laments “fierce cut-throat competition” ahead. There is no schadenfreude in his tone as he reflects on the Mosel today.

“I have an image in my head that makes me very sad,” Dostert says. “The image of a winegrower. Perhaps 70 years old and having toiled on the steep slopes for 50 years. Carrying on his parents' legacy. Proud of his Riesling grapes every year. Miserable vintages. Outstanding vintages. His body marked by work. And then, at the end of his active time as a winemaker, such a structural challenge arises. Customers become fewer. Many different vintages lie relabeled in the cellar. At the same time, there are more and more documentation requirements. Digitization. His children moved to distant cities to study and have their families there. And now, with the prospect of a meager pension, all the machines he bought and all the vineyards he lovingly tended are almost worthless.”

The description fits a swath of producers who appear to have hoped the status quo would hold forever. Theirs is likely the most dangerous position to occupy in the Mosel today: family wineries that rely on customers who for decades came year after year to load their car trunks with a wide range of wines. These wines — and their prices — have not kept pace with the times. More and more are closing their doors and giving up their vineyards.

The Old Guard

Things look brighter for the Mosel old guard. Storied and widely exported wineries such as Maximin Grünhaus and Karthäuserhof in the Ruwer, Egon Müller in the Saar, J.J. Prüm, Selbach-Oster, Schloss Lieser and Dr. Loosen in the mid-Mosel can afford to take the long view. They have built diversified markets and amassed resources that enable them to withstand structural change as they preserve sites and styles without equal. Alongside them are micro-estates such as Hofgut Falkenstein, Weisser-Künstler and Julian Haart, small teams that turn out tiny quantities of plot-precise wines for cultish followings.

They are all less intent on breaking a mold than continuing the pursuit of handcraft at a human scale. They farm historic sites with practices that hew closer to those of their grandfathers than their fathers. They work in classic styles, fine-tuning with care and precision. Cask aging, long elevage and far less intervention are the new rules in the cellar. Some hold back late releases, others work on making their styles more immediately approachable. The wines are arguably more expressive and timeless than ever.

Into this mix come the trailblazers of the “Alt” or “Nouveau” Mosel: iconoclast Ulli Stein, and organic/biodynamic trailblazers Rudi Trossen and Clemens Busch. In the 1980s, this trio began to upend a stubborn belief that the Mosel’s conservative path was inscribed in stone. But it took until well into the 21st century for the outside world — let alone Germany itself — to recognize the revolution under way.

This brings us to some of the most exciting actors in the modern Mosel, several of whom trained with or were inspired by Busch, Stein or Trossen. The group includes both the younger generation of small family estates and newcomers, or Quereinsteiger as they are known in German. Among the latter, few are from the Mosel or have family connections to wine. Jakob Tennstedt, Matterne & Schmitt, Tobias Feiden, Daniel Fries, Jus Naturae, Shadowfolk, Max Kilburg, Julien Renard and Philip Lardot are just a few of the names that have gained an international following over just the past five or so years.

What this crew lacks in financial backing, they make up for in sweat equity. They bring a refreshing openness to experiences garnered in other fields and regions. Most importantly, are building a community that is international, eclectic and wholly unlike the more provincial Mosel culture of even one generation ago.

They’re also singularly positioned to take risks. They’ve embraced agroforestry projects, revived single-stake sites, launched CSAs, taken on regenerative farming, reclaimed steep slopes and revitalized old cellars, presses and casks up and down the valley.

The Mosel at a Turning Point

With new talent and terroir comes greater diversity of varieties and styles. Here it’s vital to underscore that no one in the Mosel is walking away from Riesling. Even in sites where water and heat stress, fungal disease pressure and killer frosts have become routine threats, growers remain justifiably bullish on this famously cool-climate grape. Riesling is resilient. When aided by adjustments to viticultural practices, like layering in composting protocols and reworking vine canopies to offer more shade to grapes and soils, this variety remains vital and inimitable.

Among newcomers, (almost) anything goes. One of the most notable recent shifts has been the rise of Mosel Landwein. This was once a beleaguered catchall for bottles deemed regionally “atypical.” Now growers who prize individuality over a regulatory body’s seal of approval take pride in the Landwein designation. This has opened up a world of possibilities. Wines of all stripes, from skin ferments to pet-nats to blends. Greatly reduced cellar interventions (low, right down to no added sulphur) and a fresh appreciation for hands-off winemaking have been revelations. Not every experiment succeeds, but vintage by vintage, the Landwein set is opening a new lens through which to explore Mosel terroir.

Add to this a paradigm shift in Spätburgunder (Pinot Noir), the first glimpses of the rise of Chardonnay, successful experimentation with climate-adapted PIWI varieties and time-tested historic grapes like Elbling and it is clear the Mosel will endure, its kaleidoscopic splendor refracted through new prisms, a diamond-like durability made more perfect under pressure.

|

With this context in mind, three modern periods help clarify the twists and turns the Mosel is navigating today. 1950s-1970s Climate change has accelerated, reaching a tipping point. Ripeness is no longer a worry: preserving acidity, learning to work with nature through erratic growing seasons (drought, heavy rainfalls, humidity and frosts) are the pressing challenges. Spätburgunder (Pinot Noir) makes a serious quality leap as growers zero in on the right clones, sites and vinification techniques. Riesling is fully ascendant. Family wineries are shrinking in response to decreased wine consumption at home and abroad. Estate successors or buyers are scant. The survival of the Mosel’s distinctive cultural landscape of steep slope vineyards is imperiled. Growers are more attuned than ever to flourishing export markets. |