Matt Walls is an award-winning freelance wine writer, author and consultant who contributes to various UK and international publications such as Club Oenologique and Decanter, where he is a contributing editor. He also judges wine and food competitions, develops wine apps and presents trade and consumer tastings. Matt is interested in all areas of wine, but specialises in the Rhône Valley – he is Regional Chair for the Rhône at the Decanter World Wine Awards.

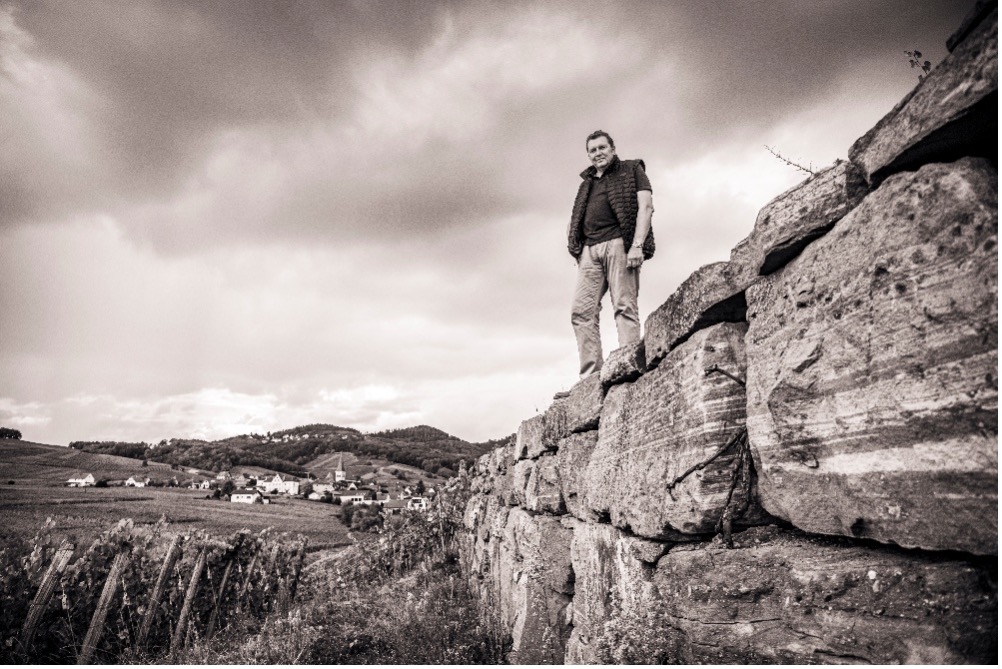

Alongside his blog contributions, Matt brings his knowledge to the vineyard as a brilliant guide for WSG’s Educational Wine Tours.