BLOG

Rosé or Blanc de Noirs? Reflections on the Chromosphere in Light of Provence

Christopher Howard

Blog

Late afternoon in Nice, almost the golden hour when the Mediterranean turns from cobalt blue to Homer's wine-dark sea. Sitting with a friend at a café, I hold up my glass of rosé to the setting sun. Platinum, not a drop of pink. 'Is this actually rosé? Seems like white wine,' I wonder aloud. 'It's made from red grapes—it's rosé. This is how they do it now,' my friend insists. The conversation drifts on as the sea and sky continue to change but the thought remains.

The Paleization of Rosé

Rosé has been getting paler since the early 2000s, and the trend shows no signs of reversing. Provence, which produces 134 million AOP bottles annually and accounts for 42% of France's rosé production, has led this chromatic evolution. With the exception of Bandol, most premium rosés are almost evanescent—what is sometimes called 'pétale de rose' or 'melon' shades.

When I spoke with Constance Savage, proprietor of Château de Mille in Luberon, she didn't think the paleization was connected to the trend toward bone dry rosé in the post pink Zinfandel era. The paleization, Savage suspects, has more to do with psychology—'I think the lightness appeals to people'.

This intuition is confirmed by research from the Centre du Rosé in Vidauban—the world's only research facility dedicated exclusively to rosé wine. Studies there have documented how consumer preferences have shifted dramatically toward lighter hues. Yet additional research suggests this trend may have limits: many people actually respond more positively to rosés with peach and melon tones than to almost colorless wines.

Why the shift from pink to pale? My hypothesis is that it corresponds to the broader movement toward lighter, fresher wines across all categories—a trend driven by multiple forces. The rise of natural wine, the embrace of native and rare varietals and the democratization of wine styles have all expanded 21st-century palates beyond the red-white dichotomy. The Parker era's deeply colored, heavily extracted reds have given way to wines better suited to contemporary cuisine.

Climate change plays a role too. Viticulturally, white and rosé grapes are harvested earlier than those destined for red wine, preserving acidity while avoiding overripeness in warming vintages. And culturally, we increasingly seek wines that lift and refresh—perhaps as a counterbalance to the heaviness of the world today.

How Rosé Gets Its Color—Or Doesn't

Rosé still comes in a remarkable spectrum of colors. The shade is largely a product of how it's made. There are three primary methods, each delivering different color intensities.

Direct pressing produces the palest wines. Red grapes are pressed immediately after harvest with minimal or no skin contact, then fermented like white wine. This extracts very little color from the grape skins, resulting in wines that can be almost colorless.

Short maceration involves leaving crushed red grapes in contact with their skins for 2 to 24 hours before pressing. The longer the contact, the more anthocyanins (color pigments) are extracted. This is the most common method and allows precise control over color intensity.

Saignée (French for 'bleeding') is a byproduct method where juice is 'bled off' from a red wine fermentation tank after a few hours of maceration, concentrating the remaining red wine while producing rosé as a secondary product. Saignée rosés tend to be darker and more structured.

The palest Provence rosés are almost exclusively made via direct pressing with protective winemaking techniques—careful temperature control, sulfur dioxide management to prevent oxidation and minimal lees contact. Some producers take it even further, using charcoal fining to strip away any remaining color. These wines are vinified essentially as white wines, which brings us back to my question from the Nice café.

Where Does Rosé End and Blanc de Noirs Begin?

Blanc de noirs is white wine made from red grapes with no skin contact—like Champagne made entirely from Pinot Noir. So when ultra pale rosés are made via direct pressing with no maceration, are they functionally blanc de noirs? The Oxford Companion to Wine notes that 'it can be almost impossible on the basis of taste alone to distinguish a rosé wine from a white one'—a remarkable admission about the fluidity of these categories.

What would happen if the ever-popular pale rosé was relabeled as blanc de noirs? Would it liberate Provence from being synonymous with a single style and allow its overshadowed reds and whites to shine? Or would it confuse people and damage the well-constructed brand that has made Provence rosé a global phenomenon?

Vigneron Peter Fischer of Domaine La Revelette in the Coteaux d'Aix en Provence has long lamented that despite being 'a major wine-growing region and the oldest in France'—Provence has been reduced to 'the simple color of rosé expressed in a standardized way around technological winemaking.'

Provence is indeed much more than pale or pink rosé. Bandol produces not only some of the region's most celebrated rosés, but also delicious Mourvèdre-based reds and elegant whites.

Nearby Cassis produces mainly white wines, while Les Baux-de-Provence, the first and only 100% organic appellation in France, focuses primarily on reds. Yet the commercial success of pale rosé, for all its global appeal, tends to eclipse this diversity.

As I explored a wide range of Provence wines, from lemon-green Vermentinos to platinum rosés and dark-as-night Mourvèdres, I began to wonder whether we have been misunderstanding the color of wine all along. What we call red, white and rosé are simple placeholders for an infinite spectrum of colors—which, as it turns out, aren't even in wine at all.

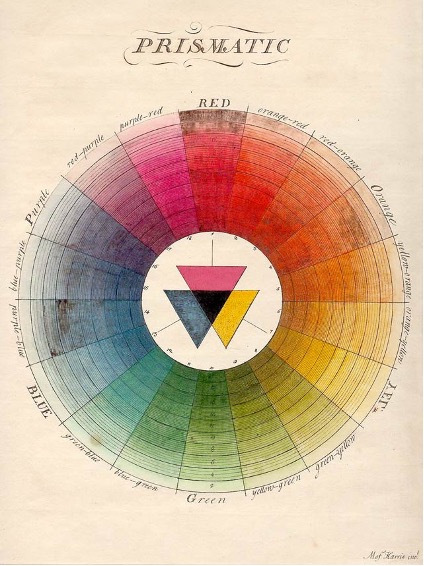

Wine through the Prism

Color is visible light of a specific wavelength. For we humans, the chromatic spectrum ranges from 700 nanometers at the red end to 400 nanometers at the violet end. That's a narrow band and we have no idea what the world would look like if the doors of perception were open wide so we could see beyond it. I, for one, do not crave such an expansion of perception. The chromatic wonders of this world are intense and overwhelming enough as it is. What we're seeing when we see colors is photons reflecting off objects. Colors do not belong to objects at all, but are what objects fail to absorb. We say the wine is red, but red is not in the wine—we see only the wavelengths that bounce off it. Color is what escapes.

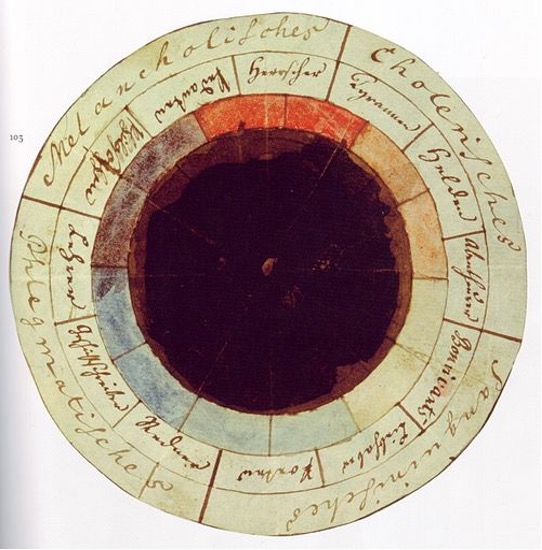

But the color of wine is more than a matter of physics—it's also a symbolic language. Provence rosé, which is as mood-inducing as it is mood-reflective, speaks that language with particular clarity. What do pale rosés evoke? Delicacy. Sophistication. Minimalism. Lightness. Elegance. There's an aesthetic of restraint in these pale wines that aligns with contemporary tastes in design, fashion and food.

There has been a trend in wine criticism to skim over wine's visual dimension, going straight to aromas and flavours. Yet things go missing when we don't linger with wine and allow it to shine forth. This starts with simple presence—not analyzing or mapping, just looking and seeing how you feel.

Provence rosé is a complete aesthetic package, evoking a specific mood, place and lifestyle. A glass of it can trigger a constellation of associations — the Mediterranean light and landscapes that captivated the Impressionists; sun-bathers and celebrities on the French Riviera. Matter and meaning can’t easily be separated and wine engages not just our senses but our memories and fantasies. The goal isn't to eliminate these in pursuit of 'objectivity,' but to become aware of them—to pay attention not just to the wine in our glass, but to the encounter itself.

Loving the Questions Themselves

Such ruminations, sparked over a glass of pale rosé with my friend in Nice, remind me of a Taoist parable. One day, Zhuangzi and his friend Huizi were strolling on a bridge over the River Hao, when Zhuangzi observed, 'See how the minnows dart between the rocks! Such is the happiness of fish.'

'You not being a fish,' said Huizi, 'how can you possibly know what makes fish happy?'

'And you not being I,' said Zhuangzi, 'how can you know that I don't know what makes fish happy?'

'If I, not being you, cannot know what you know,' replied Huizi, 'does it not follow from that very fact that you, not being a fish, cannot know what makes fish happy?'

'Let us go back,' said Zhuangzi, 'to your original question. You asked me how I knew what makes fish happy. The very fact you asked shows that you knew I knew—as I did know, from my own feelings on this bridge.'

The anecdote is usually taken as a confrontation between two irreconcilable approaches to the world: the logician versus the mystic. But if that's true, then why did Zhuangzi, who wrote it down, show himself to be defeated by his logician friend?

After thinking about the story for years, it struck me that this was the entire point. By all accounts, Zhuangzi and Huizi were the best of friends. They liked to spend hours arguing like this. Surely, that was what Zhuangzi was really getting at. We can each understand what the other is feeling because, arguing about the fish, we are doing exactly what the fish are doing: having fun, doing something we do well for the sheer pleasure of doing it. Engaging in a form of play.

Wine, despite its air of seriousness, invites the same kind of play. Does it actually matter whether we call these pale Provence wines rosé or blanc de noirs? Probably not. But thinking about such questions, having friendly debates about wine trends and interrogating our assumptions is part of the fun. Wine is sensual and cerebral, symbolic and material. We derive pleasure not by untangling all these dimensions, but by lingering with them and seeing where they take us.