BLOG

The 10 Crus of Beaujolais: What Do They Share? How Do They Differ?

Wine Scholar Guild

Regional Spotlight

Over the past 20 years, the restoration of Beaujolais has been one of the great success stories in French wine. For decades it was best known for simple Beaujolais Nouveau, rushed out for consumption on the third Thursday of November every year, but the hullaballoo around this marketing stunt is now dissipating as the potential quality of its cru wines draws the spotlight.

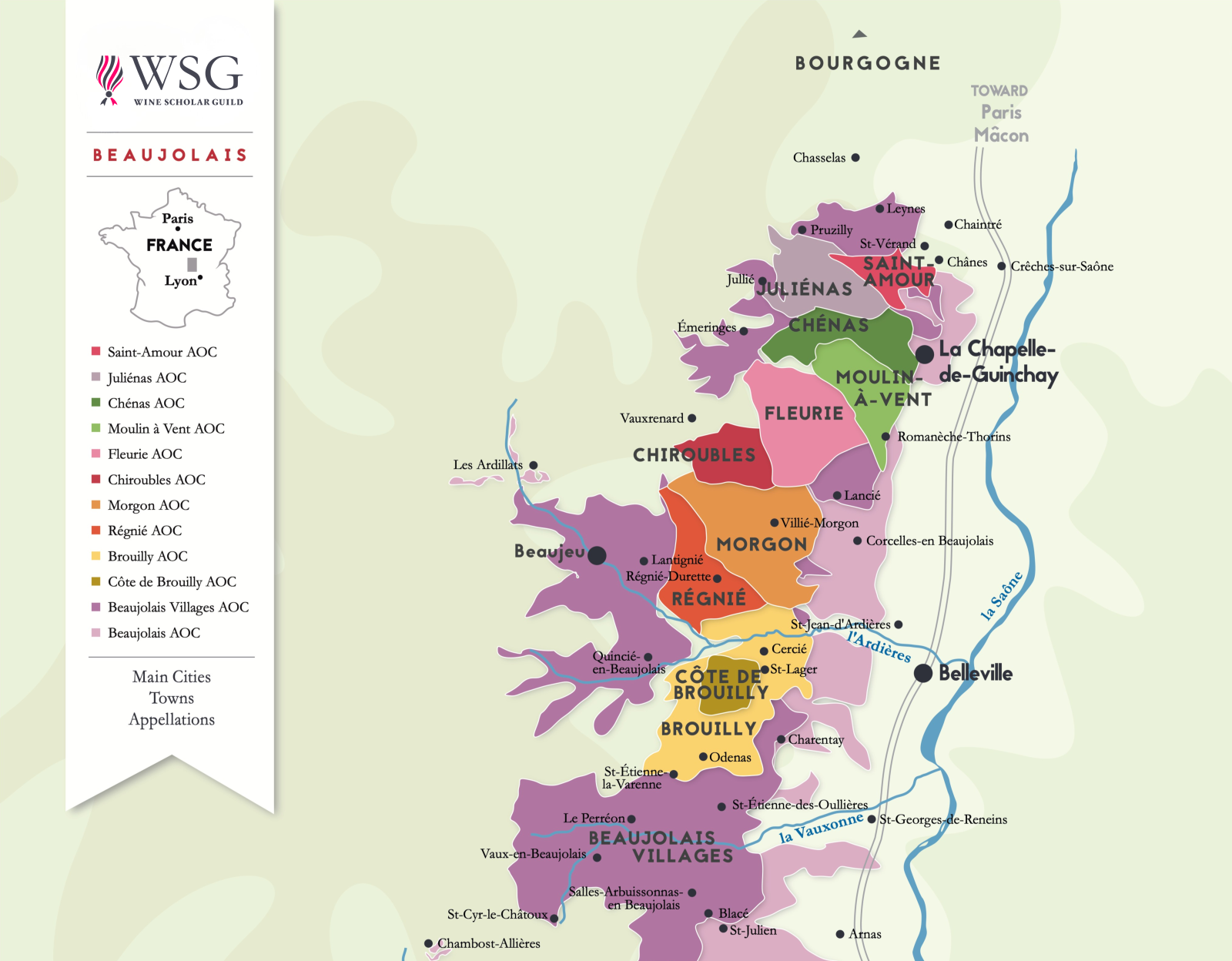

Recent soil maps have cast new light on these 10 crus, all grouped together in the northern part of the region. They share many aspects: grapes, viticulture, macroclimate. So the differences in style are essentially down to geography–which makes these wines a fascinating study in terroir.

Beaujolais and Beaujolais Villages

© Beaujolais Wines/Etienne Ramousse

Like many of France’s wine regions, the Beaujolais wine classification has a pyramid structure. Beaujolais AOC is the most forgiving in terms of its rule book and covers the largest area: 85 villages (or communes, to be more precise) between the city of Lyon and the Mâconnais on the west bank of the Saône River.

Theoretically a step up in quality, Beaujolais Villages AOC stipulates lower yields, higher minimum alcohol levels and covers the best 38 communes of Beaujolais AOC’s 85.

Both of these Beaujolais appellations can create red, rosé or white wine (whites must be made from pure Chardonnay).

The 10 crus: what do they share?

The Beaujolais crus sit above these two larger appellations at the top of the quality pyramid, and all 10 share a host of attributes.

All 10 make still, dry, red wines only. They all follow a very similar cahier des charges (production rule book).

They share the same continental macroclimate.

The main grape used is Gamay. Its full name is Gamay Noir à Jus Blanc, pointing out that it has black skin and clear juice, to set it apart from two red-fleshed varieties that are also permitted in small quantities (up to 10% in total): Gamay de Bouze and Gamay de Chaudenay.

In the vineyard, plants are mostly grown as bushvines (though trellising as cordon de Royat is permitted) and they can live to over 100 years old. All the 10 crus are divided up into dozens of lieux-dits.

In the winery, producers can choose from carbonic maceration, semi-carbonic maceration or traditional vinification. Most use concrete tanks to ferment, and mature their wines in old oak foudres.

The 10 crus: what differentiates them?

So in what way are the crus different from each other? It’s mostly down to soil type and the shape of the terrain: altitude, aspect and gradient. Along with microclimatic influences, these are the main variables that create the subtle differences in style between them.

North to south, the 10 Beaujolais crus explained

Saint-Amour

Total vineyard area: 310 ha/770 ac

Average elevation: 335 m/1,100 ft

This most northerly of the Beaujolais crus takes its name from a Roman soldier who fled to France in the 3rd century and established a monastery here. It’s a signature that has proved extremely useful when it comes to sales and marketing.

It has the gentlest slopes in Beaujolais and some of the most diverse soils, with pink granite (the region’s most emblematic substrate), blue diorite, clay, sandstone and alluvial deposits. As such, it’s difficult to generalize about the characteristic style of Saint-Amour, but it tends to be towards the lighter end of the scale, fresh and aerial.

Juliénas

Total vineyard area: 540 ha/1,330 ac

Average elevation: 330 m/1,080 ft

The name Juliénas probably derives from Julius Caesar, who made a stopover here during the Gallic wars.

While much steeper than neighboring Saint-Amour, Juliénas also has very diverse soils. It is the least granitic of all the crus; instead, it has plentiful schist, blue diorite, sandstone, clay and alluvials. In her book The Wines of Beaujolais, Natasha Hughes MW says that the diorite-rich soils “lend the wines a certain breadth on the palate and firmness of tannin”. Its hilly terrain provides multiple exposures, with the most favored sites being those that face south and southeast.

Chénas

Total vineyard area: 220 ha/540 ac

Average elevation: 250 m/820 ft

There are two theories about where Chénas gets its name. It was once covered with oak trees, known as chênes in French; or it could refer to a Roman family that lived here named Canus.

It’s the smallest of all the Beaujolais crus and its terrain varies substantially from west to east. The west is made up of very steep granite hills; the east features pebbly alluvial soils with gentler slopes. Expect more black fruit flavors than its neighbors and firmer tannins, making for a cru with good ageing potential.

Moulin-à-Vent

Total vineyard area: 620 ha/1,530 ac

Average elevation: 255 m/840 ft

There is indeed a moulin-à-vent (windmill) in this cru; it dates back to the 15th century and is a protected historical monument. It goes to show this has always been a windy spot, which is useful for keeping fungal diseases at bay. It might surprise therefore that this is one of the lowest-lying Beaujolais crus. Its slopes are gentle, but they face south- and southeast, capturing the sun.

Moulin-à-Vent was famous for the quality of its wines in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and today it produces some of finest, longest-lived wines in Beaujolais, with Hughes praising the wines for their combination of fine, grippy tannins, peppery aromatics and floral notes.

The northwestern part is mainly pink granite; to the east, the soils have more clay and ancient alluvial and colluvial deposits. There is also a large band of manganese that some producers claim plays an important part in the cru’s typicity.

Fleurie

Total vineyard area: 790 ha/1,950 ac

Average elevation: 340 m/1,120 ft

Fleurie’s terroir is characterized by two things. First, the steepness of its slopes. Second, the amount of pink granite that underpins its vineyards–over 90% of its surface. The remaining area, two outcrops to the east, is alluvial deposits.

The poor, acidic granite soil is more or less weathered depending on the location. Where it’s decomposed into granitic sands it can make for a very dry, draining terrain; an advantage in wet years, but less beneficial in dry weather.

Its name refers to the typical style of wine found here, particularly from the more elevated vineyards: delicate, red-fruited, with a pronounced floral aroma. The wines from lower down the slopes, where there’s more clay, tend to be slightly fuller and more structured.

Chiroubles

Total vineyard area: 280 ha/690 ac

Average elevation: 410 m/1,350 ft

Directly southwest of Fleurie is Chiroubles. Like its famous neighbor, it’s also very steep, with plots rising from 270m to 600m. It’s also made up almost entirely of pink granite, very thin and sandy in places. Unfortunately it’s an area particularly prone to hailstorms.

It’s less than half the size of Fleurie, which might explain why, despite the similar terroir and quality potential, it’s not at all as well known. Hughes describes the style here as one of “finesse, tension and a heady perfume”.

Morgon

Total vineyard area: 1,060 ha/2,620 ac

Average elevation: 310 m/1,020 ft

Second only in size to Brouilly, Morgon is a particularly large cru with very diverse soils. The main type is pink granite, to the west and north, giving a relatively delicate expression. Much of the southern and western vineyards are made up of alluvial deposits and clay, which produce a richer, fruitier style. The Côte du Py, the most famous lieu-dit in Morgon (and arguably in the whole of Beaujolais), is a large outcrop of blue diorite. This terroir is the source of the denser, structured, long-lived wines for which Morgon is famous.

Apart from the Côte du Py, which rises to 358m/1,175 ft elevation, Morgon has some of the gentlest slopes among the Beaujolais crus.

Régnié

Total vineyard area: 380 ha/940 ac

Average elevation: 350 m/1,150 ft

It was the discovery of a Gallo-Roman villa belonging to a nobleman named Reginus that confirmed the origin of the name of this cru. It’s the most recent of the 10 to be promoted to this top level of the appellation pyramid, in 1988.

It’s another heavily granitic appellation but it also contains large outcrops of sandstone, schist and alluvials. In terms of local style, Hughes says “most Régniés are notable for their plush, juicy character rather than their firmness of structure”.

Côte de Brouilly

Total vineyard area: 300 ha/740 ac

Average elevation: 300 m/980 ft

There are two crus with Brouilly in their name: Brouilly and Côte de Brouilly.

Brouilly is the most southerly of the Beaujolais crus, and the biggest. Its vineyards surround a small, conical hill rising to 484 m/1,588 ft that represents the cru of Côte de Brouilly–so let’s deal with that first.

It might be more straightforward if Côte de Brouilly was called Mont Brouilly, since that’s the official name of the hill over which the vineyards of Côte de Brouilly are spread.

Though granitic to the west, its most notable soil is blue diorite. Though a very hard rock, it has many cracks and fissures within it, allowing roots to delve down deeply. It typically produces powerful, ripe, black-fruited wines that age impressively.

Brouilly

Total vineyard area: 1,180 ha/2,920 ac

Average elevation: 290 m/950 ft

Surrounding the Côte de Brouilly is Brouilly, the largest cru in Beaujolais. It’s around four times the size of Côte de Brouilly and has very diverse soils. To the south and west, it’s mainly granite. The north and east are more varied, with limestone, schist, marl, alluvials and diorite.

The size and diversity of this cru make style generalization difficult, but these are largely fruity, approachable, easy-drinking wines that are usually best drunk young.

Next step: premier crus

© Beaujolais Wines/Etienne Ramousse

The many similarities between these different crus–all producing still, dry, red wines made from the Gamay grape under the same macroclimate–act as constants, helping to show how the lie of the land and its different soils influence the wine in the glass.

These 10 crus might currently represent the top level of quality in Beaujolais, but all that might be about to change. In 2024, Fleurie, Moulin-à-Vent and Brouilly all applied for their finest lieux-dits to be recognized as premier crus–and others might not be far behind.

On the surface this might appear entirely beneficial for the region and its growers, serving to further elevate the finest terroirs and wines of Beaujolais. The reality, however, is more nuanced.

Keep an eye out for our next blog, in which Natasha Hughes MW delves into the question of Beaujolais premiers crus in more detail.