BLOG

Vine to Wine: A Year of Viti/Vini - January

Nova Cadamatre MW

Wine Fundamentals

WSG launches “Vine to Wine,” an exciting, new blog series that will chronicle what is happening in the vineyard and in the winery each and every month of the calendar year. Nova Cadamatre, MW and winemaker, will author these authoritative and detailed posts drawing upon her studies (Cornell Viticulture and Enology graduate) as well as her winemaking experience in California, China and the Finger Lakes.

Each “Vine to Wine” installment will detail that month’s vineyard and winery tasks with deep dives into a particular grape growing or wine making topic such as pruning methods and training systems or barrel aging and fermentation vessels.

The series is designed to give wine students and educators an opportunity to develop or hone their technical savvy.

January is a very quiet time for the winery in the northern hemisphere. It is the in between time when the last vintage is quietly waiting in maturation and the next vintage has yet to start. In cold climates, all eyes are still on the weather to ensure that the depths of winter do not bring damage to the dormant buds. The buds hold the entire shoot and cluster primordia (more on this in February’s post) for the new vintage and each variety has a different tolerance to the cold… so monitoring the risk of damage is very important.

In warm climates, pruning usually commences as soon as the first killing frost has occurred and the vines lose the remainder of their leaves leaving only the canes (lignified shoots from the previous growing season). Since the timing of pruning has a huge impact on the timing of bud break, it is important to get the pruning schedule right. Pruning too early can cause the buds to break early and risk damaging frosts. Prune too late and the harvest can be delayed due to lower ripeness levels and/or run into problematic fall weather.

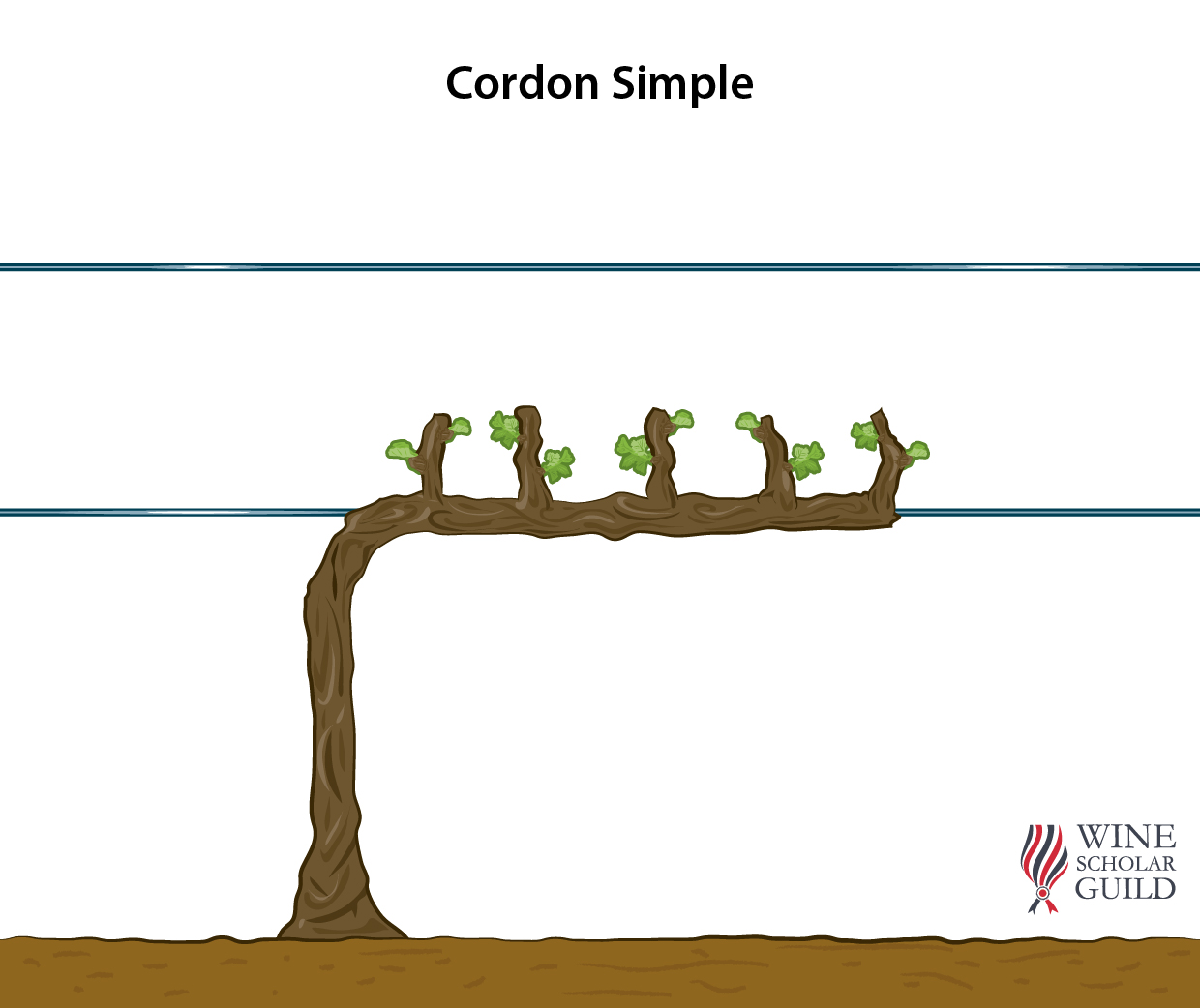

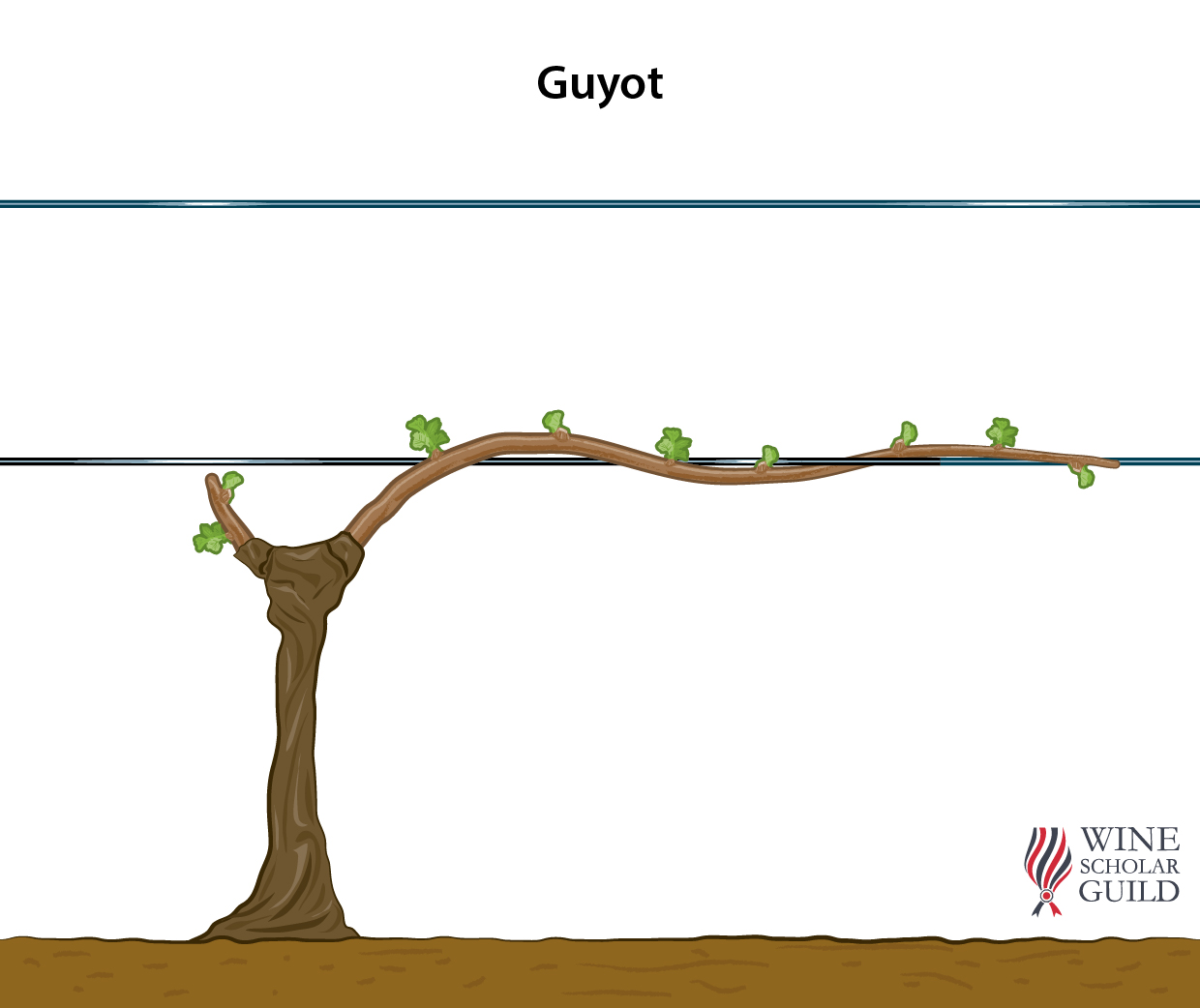

There are two types of pruning: spur and cane. Spur pruning involves one or more permanent cordons. (Besides the trunk this is the only permanent woody structure on the vine). The cordon itself bears short spurs that are pruned to 4 or less buds). The buds on the spurs will yield this year’s fruit-bearing shoots. In cane pruning, the vine is left with one or more entire canes from the previous vintage; all the rest are pruned off. The cane is then laid down on the trellis and the buds from that cane are where this year’s fruit-bearing shoots will appear. There are no cordons in cane pruning. The only woody part is the trunk.

There are several things to consider when deciding whether to spur prune or cane prune. Each method has advantages and disadvantages.

Spur pruning is much easier to learn and can be done with only semi-skilled labor. The vines can be pre-pruned with a machine to save time for the pruning crew. This pruning method also allows for a very organized fruiting zone which makes all growing season tasks easier (suckering, leafing, spraying, and green drops). Spur pruned vines also have a much greater uniformity of bud break, so the shoots and the fruit all develop at a similar pace leading to a greater chance of uniform ripeness at harvest.

In cold climates, however, low winter temperatures cause the cordons to split open. For this reason, it is not advised to use spur pruning in climates subject to winter freezes. Spur pruned vines, because of the larger number of pruning wounds, also have a greater risk of acquiring trunk diseases such as Eutypa (a disease that impacts the vascular tissue of the vine leading to stunted growth and reduced yields) so much care needs to be taken with the timing of pruning and the care of the open wounds post-pruning.

Trunk Diseases: This class of diseases include devastating maladies such as Eutypa, Crown Gall, and Esca. These diseases primarily attack the vascular tissue (more on this in April! Stay tuned) which inhibits the transport of water and sugar throughout the vine. With this transport reduced, the vine can not function as optimally as a healthy vine can which leads to a whole host of symptoms depending on the disease. Eutypa’s signature stunted growth is quite striking

Cane pruning is a much more complex pruning system because it requires very skilled labor to understand which canes to keep for the next growing season and which ones to prune off. Canes that are too small will not produce strong shoots or healthy fruit. Canes that are too large can be less fruitful also. Ideally, the canes to keep will be close in diameter to a Sharpie ® marker and originate as close as possible to the head of the vine. (The point at the top of the trunk from which either cordons or canes originate.) Cane pruned vines can have uneven bud break due to the direction of sap flow in the spring. Usually the buds on the end push first followed by the next farthest from the head of the vine and so on. This is why training systems (how the vine is organized in space) show the canes in a curved position (vs. a horizontal position). This curve slows the sap flow through the cane and helps all the buds break more uniformly.

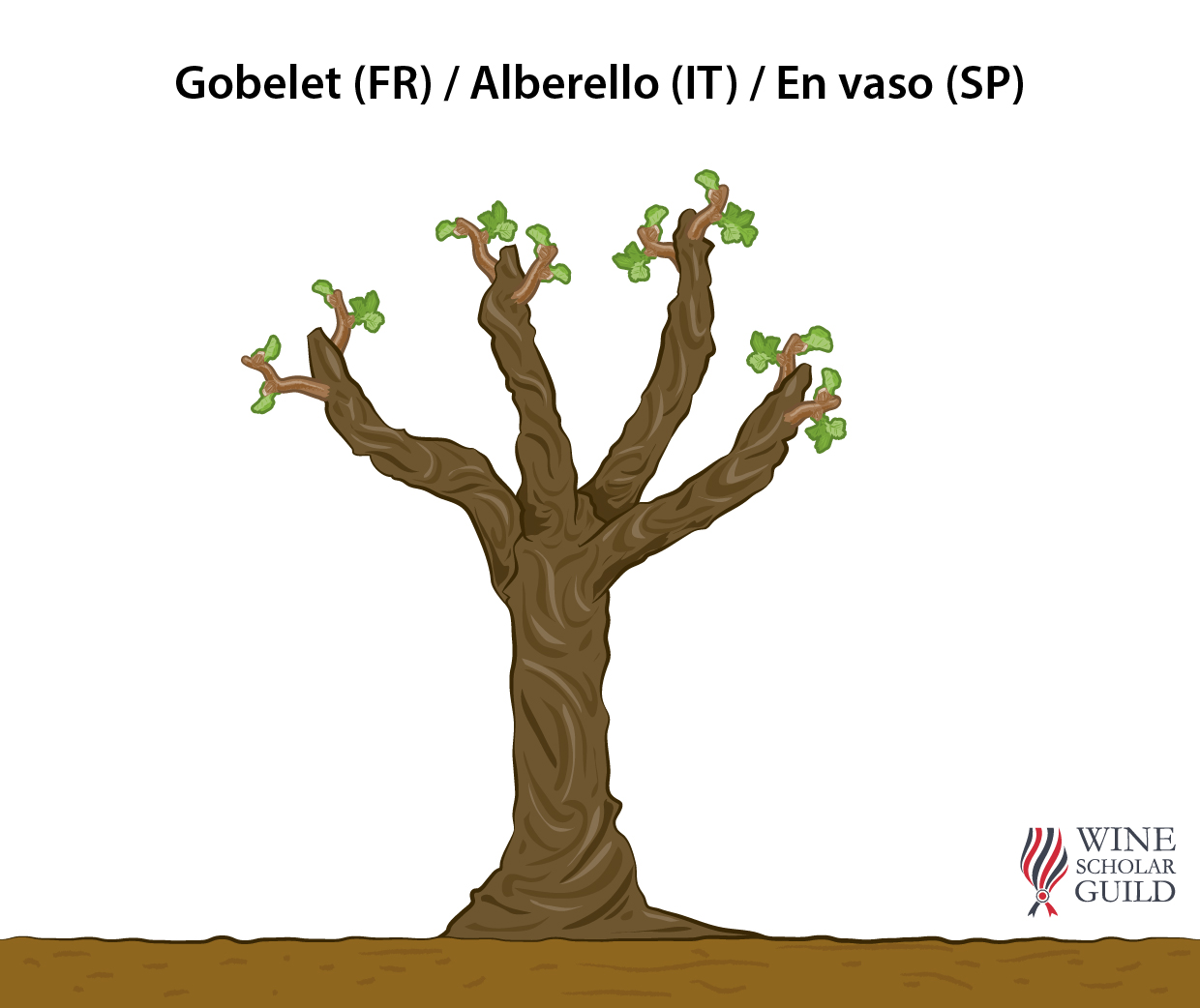

Training systems are often confused with pruning methods. While there are only two pruning methods (which we discussed above), there are many, many training methods. It is important to remember that the training method arranges the canopy. This organization can be on a supportive structure such as a trellis or stake, or without. (Head-trained vines, such as gobelet, have no support structure.)

When picking a particular training system, there are many factors to take into account: the natural growth habit of the variety, vigor of the site, pruning method, sun exposure, wind direction, and to what extent vineyard management will be mechanized. More on training systems in June!

In January, winemakers often begin blending early-release white wines or rosés, and red wines from previous vintages that will be bottled in the upcoming months. Often, the blending process starts in the lab on the bench top. It is always prudent to try many different combinations at a small lab scale to find the perfect combinations before making full scale blends in the winery. It is easy to fix mistakes made on a blend that is only 100 ml. It is less practical to do so at a full production volume.

This process can take as little as a few hours to many weeks. It all depends on the quality and size of the final blend and how well the winemaker knows each lot of wine and how these lots interact with the other lots. It is hard to say what is the most important part of winemaking since so many points of the process are critical to the final result. However, blending is the last step prior to prepping the wine for bottling, so in many cases, it is a winemaker’s last chance to improve, change, or fix anything.

Next month, we will explore risks presented by cold weather and shoot primordia in buds as well as cover crops. Our deep dive will be an exploration of oak in the winery.

MORE "VINE TO WINE" ARTICLES:

Want to know when new blog articles are released? Join this list to be notified!