BLOG

Vine to Wine: A Year of Viti/Vini - April

Nova Cadamatre MW

Wine Fundamentals

With warmer weather, bud break comes quickly. The tiny buds swell and then quickly reveal small, fuzzy, green leaves as the shoot primordia begin to elongate. These shoot primordia will become fully developed shoots over the next few weeks!

Although the exact timing of bud break varies from location to location and from year to year, cooler growing areas can have bud break as late as May; warmer regions as early as March. Either way, bud break officially starts the new vintage for the vines!

This is a particularly delicate time in the vineyard as frost can be a severely damaging event. Even though the vine has back up shoots (see February’s Viti/Vini post), severe damage to the primary shoot at this point is devastating. In mild cases, frost can delay the season since the vine has to work to replace the leaves lost. In severe instances, it means the end of the vintage. Growers work very hard to prevent frost because of this risk. Cold air drainage is top of mind when they survey prospective vineyard locations. Sites are chosen to reduce or eliminate frost pockets. If weather patterns are such that frost is a routine risk, frost mitigation equipment is employed. (see box below.)

Assuming spring comes without any adverse weather events, the shoots rapidly develop in length. The small leaves widen and develop, and the flower clusters expand in preparation for flowering.

Initially, the vine pulls from carbohydrate reserves stored in the roots and the trunk to create energy for cellular growth until the new leaves become large enough to be “exporters” of carbohydrates (typically a sugar called glucose). Usually this happens when the new leaves reach around 50% of their final size.

Until that point, the developing leaves are a sink for carbohydrates, i.e. they use more carbohydrates than they produce. Once the leaves reach 50% of their final size and larger, the leaf becomes a source of carbohydrates for the vine. These carbohydrates are transported along a network of vessels that runs throughout the vine. This vascular system is comprised of phloem and xylem. Phloem transports carbohydrates from “source to sink” wherever they are needed throughout the plant. Xylem transports water and nutrients from the roots to the shoots and is generally one directional.

Fun Fact: In grafting, the vascular system of the scion must be lined up with the vascular system of the rootstock in order to have a healthy graft. Otherwise, the transport of carbohydrates, water, and nutrients is impeded and the graft fails to take.

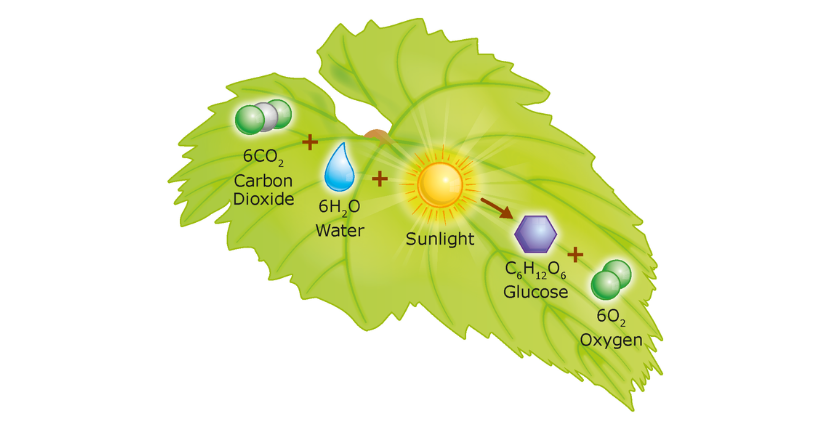

The process of photosynthesis is a fascinating one. The cells of the plant contain chlorophyll which takes sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide (CO2) and turn it into sugar (glucose), oxygen (O2), and water (H2O). It is often simplified into the chemical equation below.

The best wavelengths of light for photosynthesis are along the blue and red spectrum which is why plants are visibly green to our eyes. Green is the wavelength that the plant is reflecting back by not absorbing it. The sugar produced then gets transported through the phloem to other developing green tissues, roots, and of course, the grapes themselves which become a large sink over the course of the season.

Food for Thought: It is widely assumed that humans are the dominant and most advanced species on earth, however plants have learned to coexist in their environment and make their own food. This characteristic makes them completely self-sufficient; they do not rely on other species.

As the main shoots develop, the vine often will send up additional shoots not only from the secondary buds but also from hidden buds on the trunk or cordon. If not held in check, these extra shoots can take energy away from the principal shoots. For this reason, shoot thinning is carried out early in the season to focus and direct growth and to maintain an orderly vine structure on the trellis system.

If these extra shoots are allowed to stay, not only will the primary shoots suffer, but it will also be much harder to manage the vine as the season progresses. Airflow around the leaves and clusters will be reduced and spray penetration into the canopy will be impeded. This leads to increased disease risk and a reduced crop the following year. Remember, having sunlight on the buds is essential to the development of the cluster primordia for next year!

In the winery, this time of year is often referred to as “bottling season” which entails prepping wines for their final package. The first step towards bottling is determining the final blend. In small wineries or for single vineyard wines, this may be quite simple since the final wine may only be comprised of one lot. Larger wineries, on the other hand, may have very complex blends made up of hundreds of different components. In such instances, determining the exact proportions to make the best blend takes lots of time and work at the “bench.”

The “bench” refers to the laborious process of making tiny micro blends, sometimes only 100 ml in size, and tasting them until the exact amount of each component is determined for the final blend. It is only after many options are tried and rejected on the bench that a winemaker feels comfortable with a plan to move forward in the cellar.

After blending, the next step is fining. Fining is often confused with filtration (which we will cover in our June post). Fining is the addition of a substance to wine to remove or lessen another substance which is also present. There are many different types of fining agents including isinglass, bentonite, PVPP (polyvinylpolypyrrolidone), and egg whites and each removes something slightly different.

Bentonite is one of the more ubiquitous fining agents because it is essential to prevent protein hazes in white or rosé wines. Bentonite is a naturally occurring clay that is also used in the beauty industry for purifying masks. Egg whites remove tannin. Isinglass removes very small amounts of tannin and attaches to very small particles, pulling them out of solution to deliver a “bright” clarity. PVPP removes tannin and color compounds.

Each fining agent is chosen by a winemaker because it achieves an outcome that is more desirable than the others. Usually this is determined by a trial blend which assesses the impact of the fining agent on the wine and the quantity of fining agent that needs to be added to achieve the desired outcome.

It is important to realize that a fining agent is completely removed from the wine by clarification steps such as filtration. Even so, new EU regulations require any fining agent that is also considered an allergen, to be disclosed on the wine label even though it is no longer present in the wine itself.

What causes frost and how does frost protection work?

Frost happens on clear, still nights where the temperature reaches the dew point (the point at which water vapor in the air turns to liquid). If dew point is reached while the temperature is close to or at freezing, frost will form. Different frost protection methods work in different ways.

Frost Fans and Air Drains: These work by mixing the air. Even outside cold air sinks and warmer air rises. This means that cold pockets of still air are more likely to freeze. Frost fans work to disrupt the air stratification and keep the warmer air constantly mixing with the cooler air so that it can not settle. Air drains are upward facing fans that “pull” the cold air towards the machine and then blow it upward. This also mixes the air and does not allow cold air to settle and form frost.

Overhead sprinklers: Although this may seem counter intuitive, the water from the sprinklers freezes on the vines. At the moment the water freezes, it gives off a tiny amount of heat known as the latent heat of freezing. This heat is small, but it is just enough to protect the delicate shoots from being damaged. This can only be used in areas with ample water supply since it takes such a large amount of water to provide protection.

Smudge Pots: These work by adding additional warmth to the air. Since the pots are on the ground, the rising warm air disrupts the cold air from settling, thus preventing frost.

MORE "VINE TO WINE" ARTICLES:

Want to know when new blog articles are released? Join this list to be notified!