BLOG

The Architecture of Taste: Research Begins

Julien Camus

Insights and Opinions

On the 6th of September 2021, Wine Scholar Guild hosted the first large-scale blind-tasting panel as part of its recently announced The Architecture of Taste Research Project.

Hosted at the Bristol Hotel in Colmar, Alsace, this panel tasting launched WSG’s research on the tactile and geosensorial tasting approach it developed over the past year.

The tasting was designed specifically to assess the experimental and innovative tasting grid that had been developed as part of the Architecture of Taste Research Project. Its eventual aim is a tactile and geosensorial tasting method which focuses on a wine’s energy, induced salivation, geometry/shape, texture, and consistency.

Such a tasting method would provide students of wine with an enriched and universal lexicon that not only assesses the qualities of a wine but also dives into the nature of a wine’s personality and, perhaps, its corresponding terroir signature.

The panel of tasters included owners or representatives of twenty top Alsace estates such as Albert Boxler, Weinbach, Marcel Deiss and Albert Mann. They were joined by a dozen wine professionals, including Pascaline Lepeltier MOF, a member of the ATRP Scientific Committee, as well as a dozen serious wine lovers. All in all, over 45 panelists participated in the tasting.

The selection of wines made by WSG mainly consisted of critically acclaimed ‘terroir-driven’ or site-expressive Rieslings as well as a few field blends and two generic, supermarket Rieslings.

Different vineyard sites, mainly Grand Crus and lieux-dits, were chosen based on their geological and soil profiles. These soil profiles were predominantly based on granite, (marly-)limestone, and schist. The aim was to see if a signature could be found in the wines fermented from fruit grown on these soil types.

However, the tasting was not simply an opportunity to taste a diverse range of Alsace Rieslings, nor was it entirely focused on the attributes of the wines which might relate to soil type. The goal was also to study the usefulness of the tasting grid and to see if it helped tasters to converge and calibrate on the tasting criteria.

Each taster came equipped with a laptop or tablet in order to be able to use WSG’s own online tasting application, allowing tasters to input their impressions of the wines ‘live,’ and for statistics to be generated automatically from this data.

All wines were tasted blind and in black, opaque glasses in order to bypass, as much as possible, the sense of sight, and to help tasters focus on mouthfeel and the sense of touch.

The key questions we were trying to answer were:

- Objectivity vs. subjectivity: while using mostly abstract tasting criteria, are we able to have the same perceptions? Are there some criteria/lines of the grid where we often converge and find strong consensus? Are there some lines on the grid where we often diverge?

- Effectiveness and meaning: are certain criteria more efficient than others at delineating the personality and terroir of a wine?

- Soil signatures: are we able to find a “signature” for different soil types? Do certain wine descriptors consistently appear for Alsace Riesling wines grown in soils derived from granite, while other descriptors consistently appear for Alsace Riesling wines grown in soils derived from limestone?

In the kingdom of the blind… touch is king

Perceiving the ‘intimate personality’ of a wine, the aesthetic intention of the vigneron and the signature of its terroir requires the taster to be ready to welcome and receive it.

In order to aid full awareness and concentration, tasters were first invited to put on blindfolds and relax by breathing slowly and steadily.

Then two wines were tasted without removing the blindfolds. Participants were also invited not to start by smelling the wines, but to put them directly in their mouths and keep the wine there while being asked the following questions: “Does this wine have energy or not? Is it a cold or warm object? Is it a bright or dark object? Does it stimulate saliva-production or not? Is your salivation defensive or welcoming? Is the wine vertical or horizontal? Sharp or broad? Spherical or square? Angular or rounded? Thin or thick? Fluid or enveloping? Light or heavy? Irritating or caressing? Grainy or smooth? Tense or relaxed? Tight or loose? Juicy or creamy? Slim or robust? Firm or supple?

These terms had not been explained nor defined in order to get tasters to try to answer these questions intuitively and spontaneously.

With no initial visual or olfactory context, impressions of the wine must principally be gathered from the palate in a tactile tasting approach. The blindfold approach was adopted to shield the participants from distractions and to help them focus on their mouthfeel perceptions.

Unveiling the mask… and exposing the grid

Once everyone was made aware of their own abilities to feel and interpret a wide range of tactile sensations on the palate alone, it was time to calibrate palates on the tasting grid that would be used throughout the day.

Two additional wines were then served blind in black glasses:

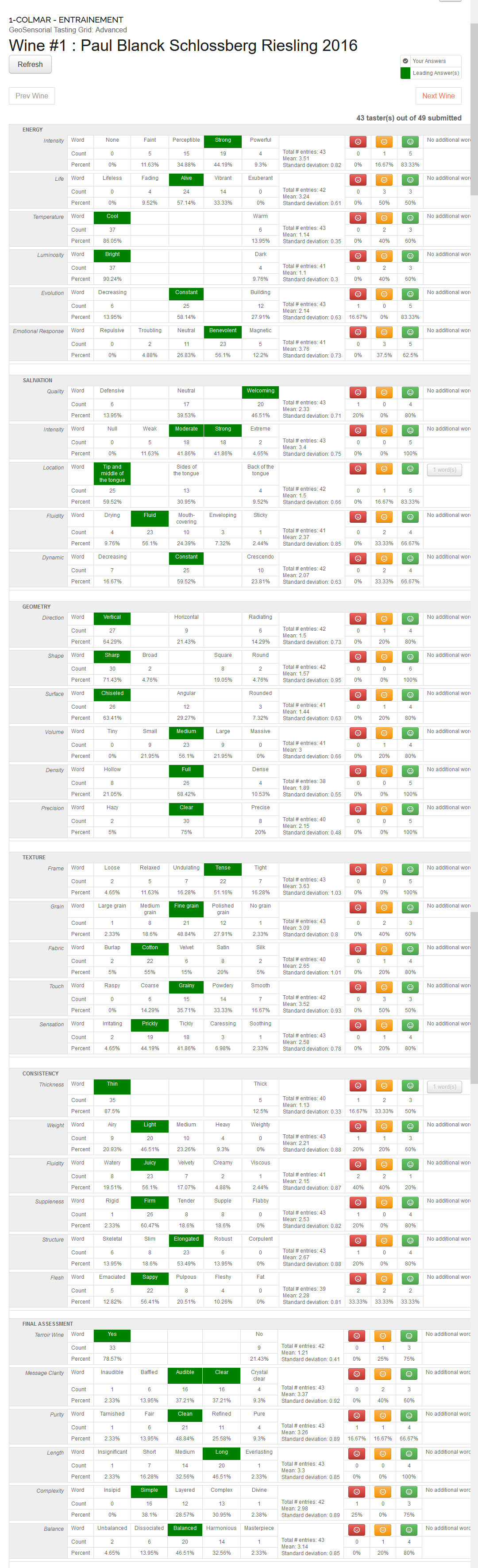

- Wine #1: 2016 Domaine Paul Blanck Riesling Grand Cru Schlossberg (south-facing granite soils)

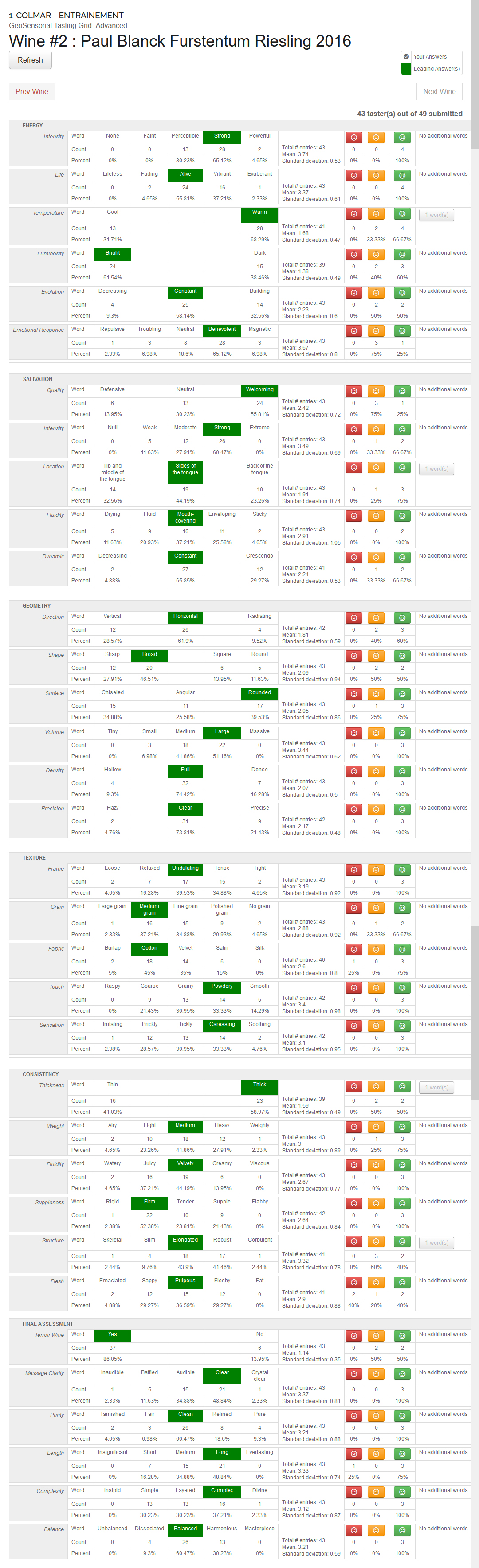

- Wine #2: 2016 Domaine Paul Blanck Riesling Grand Cru Furstentum (another south-facing vineyard located just a few hundred meters away, but this time on marly-limestone).

We tasted each wine successively and allowed each taster to enter their responses on the online grid.

Once all tasters had submitted their choices, statistics for wine #1 and later wine #2 appeared on every taster’s screen and were projected on the wall. The objective was to allow participants to discover the tasting grid (over 80 per cent of them had never seen it before) and to discuss each line of the grid having used it.

Before discussing the result of this “warm-up” set of wines, let’s take a look at the tasting grid that was used. The tasting grid was used in its original French version as all of the tasters were French-speakers.

Click HERE to view the tasting grid (full screen)

Notes on the grid above:

- The grid deliberately does not include the standard analytical tasting criteria (sight, aroma, and structural components of wine) in an attempt to focus solely on alternative tactile tasting criteria.

- The grid shown below in English still requires some fine-tuning as some French concepts do not translate easily into English

- The grid is imperfect and is a work-in-progress: we hope to find better alternatives for some words such as “heavy”, “sappy”, etc.

- A definition of each term is/was available to tasters using the French version of the grid by placing the cursor over any term on the grid

- The red, orange and red smiley icons were meant for panelists to tell us about their level comfort and certainty for the various descriptors they had picked. Unfortunately, very few panelists systematically used these icons.

A few weeks prior to this tasting, 160 Wine Scholar Guild instructors had been surveyed concerning tasting methodologies. The educators were notably asked to react to the following statements:

- “Granite wines tend to be vertical, sharp, chiseled, thin, fluid and grainy”

- “Limestone wines tend to be horizontal, broad, angular, mouth-covering and powdery”

- “Clay wines tend to be horizontal, broad, rounded, thick and smooth”

(Ten per cent of those surveyed disagreed, 17 per cent were doubtful, 35 per cent were intrigued, 30 per cent somewhat agreed and eight per cent agreed)

This phraseology was based on the course teachings of the first edition of a University Degree in Geosensorial Tasting offered by the Geology Department of the University of Strasbourg. This took place in 2019-2020 in Alsace.

Would any of the above show up once the data was computed?

Click on the grid to view it full screen!

Note on the statistical report above: On the screen of each of the panelists, the statistics shown above would also include a checkmark icon next to each word the panelist had selected… allowing him/her to compare his/her entries to the rest of the panel.

These were the most frequently used descriptors concerning each wine, with those descriptors marking contrasting impressions according to soil type in bold:

Schlossberg (soils derived from granite):

Strong energy, alive, cool object, bright, benevolent. A moderate to strong welcoming salivation, the tip and center of the tongue are mostly stimulated, a fluid, vertical, sharp and chiseled wine. It is full in density and medium in volume. A tense, grainy and prickly texture. A thin, light, juicy, firm, elongated and sappy consistency.

Furstentum (marly-limestone):

Strong energy, alive, warm object, bright, benevolent. A strong welcoming salivation, the sides of the tongue are mostly stimulated, a mouth-covering, horizontal, broad and rounded (some divergence here though) wine. It is full and large volume. An undulating, powdery and caressing texture. A thick, medium-weight, velvety, firm, elongated and pulpy consistency.

How much of these differences are due to soil vs mesoclimate, precocity of each parcel or slight differences in viticultural or vinification decisions made by the vigneron? Hard to answer. One thing is certain, though: with a purely analytical tasting grid, these two wines would have looked very similar if not the same and probably checked all the same boxes: dry, high acid, medium body, medium alcohol.

The effect of this instantaneous statistical feedback was very empowering. It made the whole tasting process a very inclusive, transparent, and democratic experience. Each taster has the same weight. They can hopefully see a consensus being formulated and are able to discuss it and compare themselves to the group.

An article discussing the findings of our statistical analysis of the 25 wines tasted during the rest of the day (after these two warm-up wines) will be published shortly.

More about the Architecture of Taste Research Project